Over the past few weeks, there has been a string of announcements from nontraditional TV distributors highlighting their ambitions to capitalize on the shift from traditional TV to over-the-top distribution. Verizon set a new benchmark for OTT sports right deals, paying $500 million a year—more than double its previous contract—to acquire mobile streaming rights to most NFL games. T-Mobile responded with the purchase of Layer3, a startup that provides a bandwidth-efficient cable-like pay TV package over other providers’ last-mile networks. And regulatory approval permitting, Disney agreed to buy most of Fox’s entertainment assets, largely to bolster its planned direct-to-consumer over-the-top offerings (which may cannibalize its still-lucrative traditional pay TV channels). Meanwhile, even the supposed “killer app” of traditional TV, the NFL, saw a second straight season of declining ratings. Taken together, these developments raise the question: What would it take for the NFL to follow in Disney’s footsteps and go direct-to-consumer?

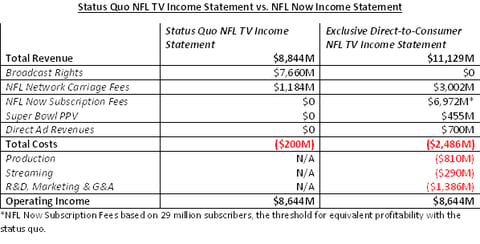

To get to an answer, we tallied up the potential revenues and costs for the NFL to go direct-to-consumer, and compared them to the economics of the NFL’s current TV deals. In this thought experiment, we assume the NFL distributes games exclusively via direct-to-consumer rather than spreading its bets across different partners. This would be out of character for the NFL but similar to what Disney is pursuing, as it is not renewing its distribution deal with Netflix.

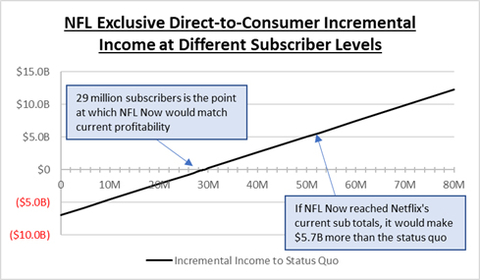

The number we get to is about 29 million paid subscribers. This is a bit more than half Netflix’s U.S. subscriber base, and similar to the audience for a typical NFL playoff game. It’s a high threshold—no livestreaming MVPD has much more than 2 million paid subscribers today—but not insurmountable.

Here’s how we got to that number:

- First, we tallied up the NFL’s current revenues from its TV deals. The NFL makes $7.7 billion a year from its current broadcasting deals. Most of that is from CBS, Fox, NBC, ESPN and DirecTV, who each pay between $1.2 billion and $2 billion annually for various packages of games[1]. Additionally, the NFL makes another $1.2 billion from carriage fees for the league-owned NFL Network, which the NFL launched in 2003, as much for leverage in TV rights negotiations as it did for generating profits. Total 2016 NFL TV revenues: $8.8 billion.

- Next, we estimated the NFL’s current operating costs associated with its TV deals. Since the basis of the NFL’s TV model is to maximize profit and minimize financial risk, these costs are not likely much—the NFL does not pay for production or delivery of games. The NFL Network broadcasts 13 games a year, which are estimated to cost the Network about $1 million apiece. Being conservative and assuming lots of other production, administrative and on-air talent costs, we estimate the NFL’s current TV operating costs are $200 million a year.

- Moving to the NFL’s exclusive OTT offering—let’s call it NFL Now—the first thing we need to estimate is the monthly subscription fee. We expect the NFL would only offer a full-season subscription, similar to MLB Extra Innings and NFL Sunday Ticket. We also expect the NFL would provide year-round programming, as it does with the NFL Network, and call the subscription fee an “annual” subscription, despite the season only lasting six months. NFL Sunday Ticket—which would not be as comprehensive an offering as NFL Now—costs fans $270 a year, while full-season packages of Major League Baseball and NBA games range from $85 to $210 a year. MVPD options from DISH (Sling TV), AT&T (DirecTV NOW) and Google (YouTube TV) cost around $420 a year. Since any scenario where the NFL would go OTT would require consumer-friendly pricing to rapidly attract viewers, we (very) conservatively estimate the subscription fee for NFL Now would be $20/month, or $240/year.

- Additionally, we expect the NFL would offer the Super Bowl as a one-off pay-per-view event for the tens of millions of people who watch little football the rest of the year. Since the Super Bowl regularly attracts more than 50 million viewing households, we would expect a PPV Super Bowl to be at least as popular as the most popular pay-per-view event of all time: the 2015 Mayweather-Pacquiao fight. At $99 a pop and 4.6 million buys that fight, we would expect a PPV Super Bowl to generate at least $455 million.

- Once the NFL is responsible for production and delivery, it will also be responsible for selling ad inventory. Standard Media Index estimated that the four major content rights holders for the NFL—CBS, Fox, NBC and ESPN— $3.5 billion in ad revenue from NFL games in 2016. The number was probably a bit lower in 2017, due to givebacks because of declining ratings. Additionally, nobody has yet been able to sell online video ads at close to traditional TV rates, so we assume that the NFL can capture no more than 20% of what NFL rights holders sell today. NFL Now advertising revenue: $700 million.

- A counterintuitive source of additional revenue for the NFL in our hypothetical scenario would be additional carriage fees for the NFL Network. An exclusively direct-to-consumer move by the NFL would seriously disrupt the pay TV ecosystem: it would dramatically reduce the leverage current rights owners ESPN, NBC, CBS and Fox have to command higher fees from pay TV distributors. The disappearance of the NFL from traditional pay TV would also likely mean a massive acceleration of cord cutting. Pay TV distributors would therefore be more than happy to expand the NFL Network’s distribution to their full subscriber bases and would probably pay whatever the NFL wanted to carry the network—after all, they would be paying one network for what they pay four for today. Being conservative, and assuming accelerated cord cutting regardless, let’s assume the NFL Network expands to a shrunken pay TV universe of 90 million homes at double its current carriage fee of $1.39 per subscriber per month. Not addressed in this analysis, but worth noting: NFL Network carriage fees will have an inverse relationship with the size of NFL Now’s subscriber base, as the fewer people who subscribe to NFL Now, the more people who will have to rely on traditional pay TV to watch NFL games. The NFL Network would act, in effect, as insurance against slow uptake of NFL Now. NFL Network carriage revenues in an NFL Now world: $3 billion.

- Now, onto NFL Now costs. The first major cost the NFL would assume that it does not today is the television production of games. As noted earlier, the NFL is estimated to spend $1 million per game on production costs. Since they share costs with their production partners, let’s double full game costs to $2 million, and assume the NFL would spend that on every regular season and preseason game. ESPN was estimated to spend $8 million on a college football championship game a few years ago, so let’s assume the NFL spends that on each of the 10 non-Super Bowl playoff games. And let’s assume they more than double that and spend $20 million producing the Super Bowl (which is separate from the costs of the halftime show and other game-related activities the NFL currently pays for). Let’s also throw in a conservatively high $2 million average salary for each announcer in the booth. NFL Now TV production cost: $810 million.

- Additionally, the NFL would need to pay for streaming media delivery, including encoding, transcoding and a content delivery network. Netflix is probably the best comp as (1) they’re the only public pure-play OTT video provider that reports any metrics on this front and (2) they’re the only player whose audience sizes would be similar to the NFL’s. They’re not a perfect match because NFL Now would be broadcasting live, which is a more complex streaming feat than unicasting pre-recorded video files, as Netflix does—although the total hours of programming encoded and transcoded would be far fewer. Netflix spent $2.9 billion on U.S. content and streaming in 2016 and says that the vast majority of this was for content. So, assuming they spent 10% on streaming, let’s say NFL Now delivery costs are $290 million.

- Lastly, onto the major fixed cost buckets: marketing, R&D and general and administrative costs. Again, looking to Netflix, we assume equivalent marketing costs to Netflix’s 2016 U.S. marketing costs—$382 million—as the NFL is similar to Netflix in that the brand mostly sells itself (and the NFL gets sponsors to pay most of its marketing costs anyway). For R&D, we assume the NFL would spend half of what Netflix spent in 2016, or $426 million, due to Netflix’s higher propensity for innovation. For general and administrative, we again assume Netflix’s $577 million spent in 2016 (which is also similar to what AMC Networks spent on G&A in 2016). Total NFL Now marketing, R&D and G&A costs: $1.4 billion.

Taken all together, you get an operating income of $8.6 billion for the status quo arrangement, which translates to a 98% operating margin. (Nice work if you can get it.) For the NFL Now scenario to match this level of absolute profit, the service would need to generate nearly $7 billion in revenue, or 29 million subscribers a year.

The upside is even greater: if the NFL could approach Netflix’s current subscriber base in the U.S.—52.8 million and counting—the league could earn an additional $5 billion beyond what it earns today:

Of course, the NFL is unlikely to pursue this path any time soon, despite its recent threat to move Thursday night games to the internet. For one, none of its major TV contracts expire until 2022. Operationally, the challenges are immense: The NFL would have to build a world-class broadcasting, advertising and technology organization more or less from scratch. Technologically, live streaming games isn’t yet a flawless substitute for traditionally broadcast games. And no major sports league in the world has undertaken something similar. (The WWE Network doesn’t count.) And legally, who knows if moving distribution in-house would jeopardize the league’s antitrust provision that allows it to maintain a hard salary cap?

Just as importantly, it would be completely out of character for the NFL to take on this kind of financial risk. The NFL has brilliantly used a game of broadcast rights musical chairs to bid up rights contracts ever higher—so high, in fact, that none of its TV partners earn back in advertising revenues what they spend in TV rights (with the exception of whoever happens to get the Super Bowl in a given year). For the longtime holders of NFL rights, it’s a matter of survival. The NFL is about the only type of programming left that is both immune to time-shifting and guaranteed to deliver large weekly audiences. Economic rationality goes out the window when you’re trying to maintain rising programming fees to counteract a shrinking pay TV subscriber base. Yet the NFL never lacks for a new entrant who sees professional football as the ticket to relevance. In the ’80s, it was ESPN and TNT. In the ’90s, it was DirecTV and Fox. Today it’s Verizon. As long as there are more players than chairs, the NFL will keep playing the same old tune.

Micah Sachs is a principal at CMA Strategy, a boutique consulting firm that advises providers and investors in the telecommunications, media and information technology markets. CMA provides a range of services for clients, from acquisition due diligence to corporate growth strategies to go-to-market planning. Micah’s areas of expertise include cable, wireline and wireless infrastructure, telecom regulation, commercial services, and voice. He can be reached at [email protected].

[1] The NFL currently receives $1.33 billion a year from CBS for AFC games, the AFC playoffs and five Thursday night games; $1.1 billion a year from Fox for NFC games and the NFC playoffs; $1.18 billion from NBC for Sunday Night Football, five Thursday night games and some playoff games; $2 billion from ESPN for Monday Night Football and one playoff game; $1.5 billion from DirecTV for the exclusive rights to out-of-market regular-season games; $50 million from Amazon for 11 Thursday night games; and $500 million from Verizon for mobile rights to most games.